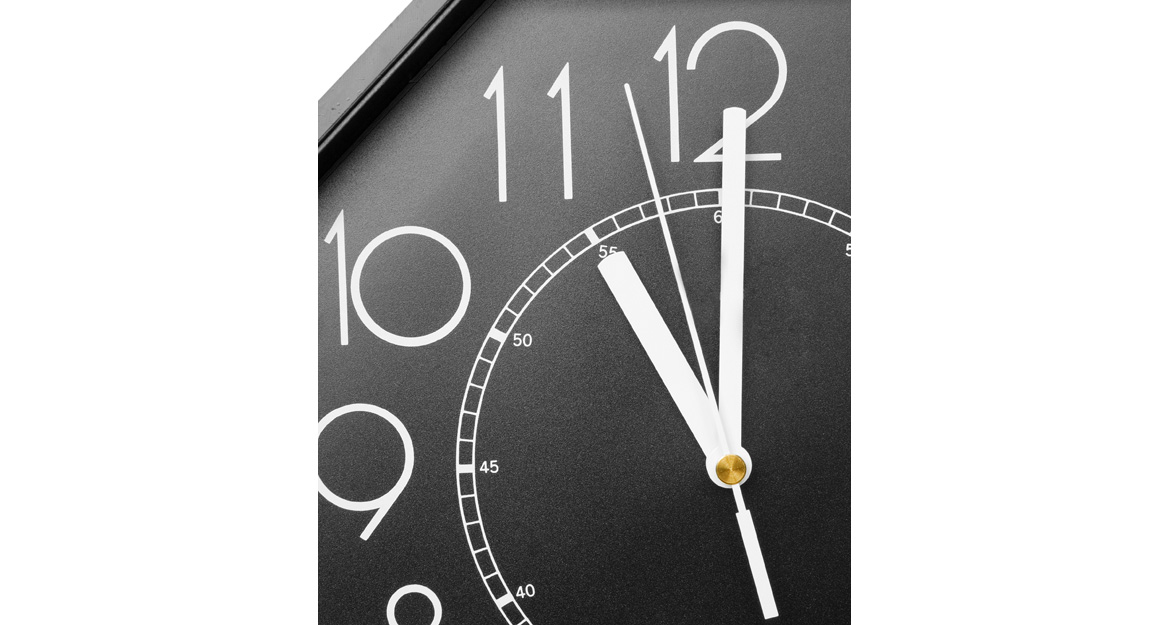

Negotiations stretch to the 11th hour as another deadline approaches, and is gone. June 30, 2015: the negotiating parties (Iran and P5+1 – China, France, Germany, Russia, United Kingdom and United States) once again were left with two options: extend the time, or walk away from negotiations.

This time the extension is only seven days. Perhaps one reason is to stick with the 30-day US congress review period of any deal, rather than the 60-day review period. Some commentators state that the parties are very close to an historic agreement, while others believe that the gap between parties’ key demands – mainly transparency over Iran’s nuclear program, and the process of sanction relief – is so wide that an agreement is beyond reach at this point in time.

In the scenario that the gap between key elements is too wide, one extra week will do nothing to aid in reaching an agreement.

However, if there is an overall understanding that an agreement should be (and can be) reached based on the Lausanne framework understanding, then the extra week may be useful.

In reality, all parties within the negotiation (in particular Iran and the US) understand the necessity of an agreement. Besides, they both have invested so much political capital in reaching a deal, that going back to the pre-negotiation status – the US imposing the sanction regime, and Iran enriching uranium – is undesirable for all parties. The key issue here is that any agreement has to be sellable to each party’s constituents. While parties reached a framework understanding in Lausanne, the key issue in this phase of negotiation (April to June 2015 plus the extra time) is playing with words. How could the text of an agreement possibly be written to satisfy parties’ Red Lines? Each party should be able to show its constituents that it did not compromise on the publicly stated Red Lines.

How such an agreement can be worded so that all parties can interpret and sell it to their own constituents, opposition and other stakeholders, without the agreement looking like a compromise, and without crossing Red Lines?

I have been discussing in “Hostile Intentions: an Agreement Based on Mutual Distrust”, the danger of drawing red lines, or bottom lines. Neither party can afford to be seen as the reason negotiation failed – any party perceived as such will likely pay a heavy price. The US may lose sympathy and collaboration from allies to increase the pressure on Iran; Iran may find more pressure applied by a more strongly unified international community.

This kind of last-minute bargaining and agreements (often taken as a sign of a ‘Reluctant Factor’ ), when combined with publicly stated Red Lines, is a dangerous gamble. Red Lines resulted from miscalculating one’s power and underestimating the other side’s options to walk away from negotiation, and can lead to incorrect negotiation strategy and consequently risky tactics.

During these last minutes, parties have left with one choice: come up with an agreement, or walk away from negotiation. Since a common understanding and interpretation of the negotiated outcome is critical in this stage of the negotiation, the key issue in this phase is the lack of flexibility of being able to interpret the controversial topics in a sellable format to one’s party. This is due to the publicly stated Red Lines – a situation that did not exist in Lausanne framework understanding.

Any last-minute agreement – when parties sees no choice but to temporarily agree to an outcome that is better than any other available alternative – will result in a risky agreement with problematic implementation. It will not solve parties’ problems; at least one party is waiting to find a better solution in the future.

Failure is not an option. But in case a wise agreement cannot be reached at this point of time, is there any alternative to keep the parties from walking away from negotiation? It seems that all negotiating parties are in agreement: if a wise agreement cannot be reached, they will maintain the status quo of Iran maintaining their current level of nuclear activities and enrichment programs, and P5+1 providing limited sanction relief. This is viewed as more desirable than Iran threatening more centrifuges and enrichment programs without limitation, and the US threatening more sanctions and potential military strikes.

In case of a deadlock in current negotiations, and in order to maintain the status quo, one solution that parties may consider is a six to twelve month cooling-off period. This is where they will take a break from negotiation to instead build trust by engaging in limited diplomacy (especially between Iran and the US). They could also work on a collaborative commercial enhancement program, including a commercial framework agreement (see Hostile Intentions). Negotiators should be reminded of the dangers of going back to square one.